The following article by our Medical Director, Dr Jack Philpott, appeared in the May 2014 edition of Medicus Journal.

Chronic insomnia:

online therapies can coexist with more traditional treatments

by Dr Jack Philpott

Managing Medical Director of Sleep WA, Perth Sleep Disorders Centres

Chronic insomnia is defined by difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep for at least three nights per weekwith associated daytime impairment for a duration of at least three months (DSM V).

Three months was chosen in the new DSM definition as this seems to be a crucial cut-off time when symptoms are more likely be chronic with a history of remission and relapse over years. The prevalence of insomnia when using operational DSM V criteria has varied in population studies between 6-10 per cent. There are few longitudinal incidence studies, however it is important to conceptualise insomnia as a chronic relapsing remitting condition.

The term ‘secondary insomnia’ has also been changed in the new definition to the more favoured term of ‘co-morbid insomnia’. This overcomes the problem of causality and also implies that when treatment of the underlying psychiatric disorder and insomnia are tackled together, the therapeutic outcome is improved.

Inadequate sleep is often described by patients years prior to the onset of depression, and the severity of sleep disturbance in subjects with depression has been associated with higher risk of relapse and increased risk of suicide. The link between poor sleep and mood disorders is likely bidirectional. This bidirectional relationship is reflected in the current nosology of insomnia as co-morbid rather than secondary.

The biological reason for sleep is not well understood. However insufficient sleep has been linked with mood disorders, neurocognitive impairment and physical disorders such as hypertension. Sleep is important in memory consolidation and REM sleep appears important in emotional memory processing. There is damping of Amygdala firing in response to rechallenge to a negatively-charged emotional stimuli if REM sleep occurs in the time between first presentation and rechallenge to the stimuli. It is thought that absence of this damping effect of REM sleep is associated with the development of both post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

The International Classification Of Sleep Disorders II (2005) attempted to subtype primary insomnia into various categories including psychophysiological, paradoxical or state misperception, idiopathic and insomnia related to poor sleep hygiene. This classification of primary insomnia has been abandoned as it did not prove to be useful in clinical practice. This early attempt to phenotype insomnia was largely based on patients’ subjective reports of poor sleep. Objective measurement of sleep using PSG (increased Beta activity consistent with increased cortical arousal) and actigraphy has provided useful insights into insomnia with short sleep duration as opposed to insomnia with normal sleep duration.

Cognitive Behaviour therapy for insomnia

| Intervention | General description | Specific instructions |

| Stimulus control | BED=SLEEP. Set of instructions aimed at conditioning the patient to expect that bed is for sleeping and not other stimulating activities. Only exception is sexual activity. Aim is to promote a positive association between bedroom environment and sleepiness. | Go to bed only when sleepy/comfortable and intending to fall asleep. If unable to sleep within what feels like 15-20 minutes (without watching the clock), leave the bed and bedroom and go to another room and do non- stimulating activity. Return to bed only when comfortable enough to sleep again. Do not read, watch television talk on phone, pay bills, use electronic social media, worry or plan activities in bed. |

| Sleep-restriction therapy | Increases sleep drive and reduces time in bed lying awake. Limits the time in bed to match the patient’s average reported actual sleep time. Slowly allows more time in bed as sleep improves. | Set strict bedtime and rising schedule, limited to average expect hours of sleep reported in the averages night. Increase time in bed by 15-30 minutes when the time spent asleep is at least 85% of the allowed time in bed. Keep a fixed awake time, regardless of actual sleep duration. |

| Relaxation techniques | Various breathing techniques, visual imagery, meditation | Practise progressive muscle relaxation (at least daily). Take shorter relaxation periods (2 minutes) a number of times per day. Use breathing and self-hyponsis techniques. |

| Cognitive therapy | Identifies and targets beliefs that may be interfering with adherence to stimulus control and sleep restriction. Uses mindfulness to alter approach to sleep. | Unhelpful beliefs can include overstimation of hours of sleep required each night to maintain health; overestimation of the power of sleeping tablets; underestimation of actual sleep obtained; fear of stimulus control or sleep restriction for fear of missing the time when sleep will come. |

| Sleep hygiene education | Emphasises environmental factors, physiological factors, behaviour, habits that promote sound sleep | Avoid long naps in daytime ¬– short naps (less than half an hour) are acceptable. Exercise regularly. Maintain regular sleep – wake schedule 7 days per week (particularly wake times). Avoid stimulants (caffeine and nicotine). Limit alcohol intake, especially before bed. Avoid visual access to clock when in bed. Keep bedroom dark, quiet, clean and comfortable. |

The Penn State adult cohort has followed a group of subjects reporting insomnia with objectively measured short sleep duration compared to patients with insomnia with normal sleep duration. Short sleep duration insomnia is associated with stress-related activation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal and the sympathomimetic adrenal medullary axes. This physiological hyper-arousal seen in short sleep duration insomnia has been associated with cardiovascular morbidity and neurocognitive impairment.

In contrast, insomnia with normal sleep duration is associated with cognitive emotional and cortical arousal and sleep misperception, but not with signs of physiological arousal or cardio metabolic or neurocognitive morbidity.

This difference may help explain some of the discrepancy seen in previous population studies, which have shown variable results linking insomnia with neurocognitive impairment and cardiovascular morbidity as most of these studies did not measure sleep duration.

These phenotypically different forms of insomnia may have implications in terms of management and prognosis. (see table left)

The mainstay of treatment for insomnia is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBTi). There are over 100 peer-reviewed papers showing the positive effect of CBTi in both primary and comorbid insomnia. The availability of CBT i for the vast majority of insomnia sufferers is limited and expensive.

Recently with the advent of improved telecommunications and mobile devices, CBT has been delivered online for patients with depression and anxiety disorders with results not inferior to face-to-face delivered CBT. CBT programs are now available online for insomnia. There are many practical benefits of online CBT not the least being the convenience of therapy available 24/7 and online community support. The advent of online tailored therapy relying on advanced algorithms to tailor treatment raises questions about what are the active ingredients CBT and how many doses are needed for a good result.

There is a possible flaw in the assumption that more sessions are superior to fewer and that CBTi delivered by an expert is superior to CBTi delivered by an appropriately trained nurse or sleep technologist. It may well be that the behavioural work and cognitive changes the patient does out of session are more important than how the treatment is delivered. The delivery platform whether Internet-based, one on one or group- based sessions may not be the most important variable in terms of treatment success.

Although there are now several randomised placebo-controlled trials showing the effectiveness of online CBT for insomnia more work is needed to know if certain patient groups such as those with complex presentation or comorbid insomnia should be pre-screened for this approach.

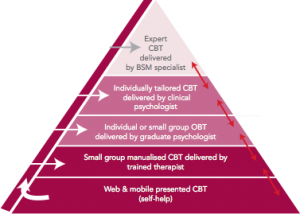

There is no reason why online therapies cannot exist alongside more traditional approaches as part of a stepped care approach to the management of insomnia as previously suggested (see diagram). Development of mobile apps (including actigraphy to objectively measure sleep) allow for rapid patient feedback and self- tracking and offer exciting possibilities for the treatment of insomnia into the future.